Fashion, at its core, is far more than a means of covering the body or following seasonal trends. It is a living, breathing form of communication that interacts dynamically with culture, history, politics, and personal identity. The clothes people wear carry stories, ideologies, memories, and even rebellions. Fashion reflects the values of a society at a specific moment in time while also contributing to its transformation. It is simultaneously shaped by the collective and the individual, offering both a mirror of societal norms and a tool for their reinvention. In a world increasingly driven by visuals, expression, and global interaction, fashion plays a vital and expansive role not only in how people present themselves to others, but in how they come to understand their own place in the world. This essay explores the deep cultural power of fashion through its historical roots, social dimensions, political impact, economic structures, and psychological depth, revealing it as one of the most complex and influential phenomena of modern life.

From the earliest civilizations, fashion has been intertwined with social order and identity. In ancient Egypt, the color and quality of one’s garments reflected social rank, with linen reserved for the elite and jewelry worn as a symbol of divine connection. In medieval Europe, sumptuary laws dictated what people could wear based on their class, forbidding the lower classes from dressing in a way that resembled nobility. Clothing, in these contexts, was not a matter of personal preference but a strictly governed expression of one’s position in society. In traditional Japan, the kimono embodied not only beauty but a philosophy of seasonal awareness, modesty, and familial heritage. In many Indigenous cultures, ceremonial dress continues to express sacred relationships with ancestors, nature, and community. These examples illustrate that fashion has long served as a language of power, distinction, and cultural belonging.

As societies grew more interconnected through trade, colonization, and migration, fashion became a site of global exchange—and often, of cultural conflict. The colonial era brought with it the spread of Western dress standards, frequently imposed on colonized populations as a means of control and assimilation. Local styles were deemed “primitive” or “unrefined” in favor of European tailoring. At the same time, colonizers themselves adopted and appropriated textiles, patterns, and aesthetics from the places they occupied, often without understanding their deeper meanings. This complex interplay continues today, where the fashion industry both borrows from and erases the origins of traditional styles. Yet resistance has always existed. Post-colonial fashion movements in Africa, South Asia, and Latin America have reclaimed indigenous dress, transforming it into powerful statements of cultural pride and political defiance. In this way, fashion not only transmits cultural heritage but actively participates in its redefinition.

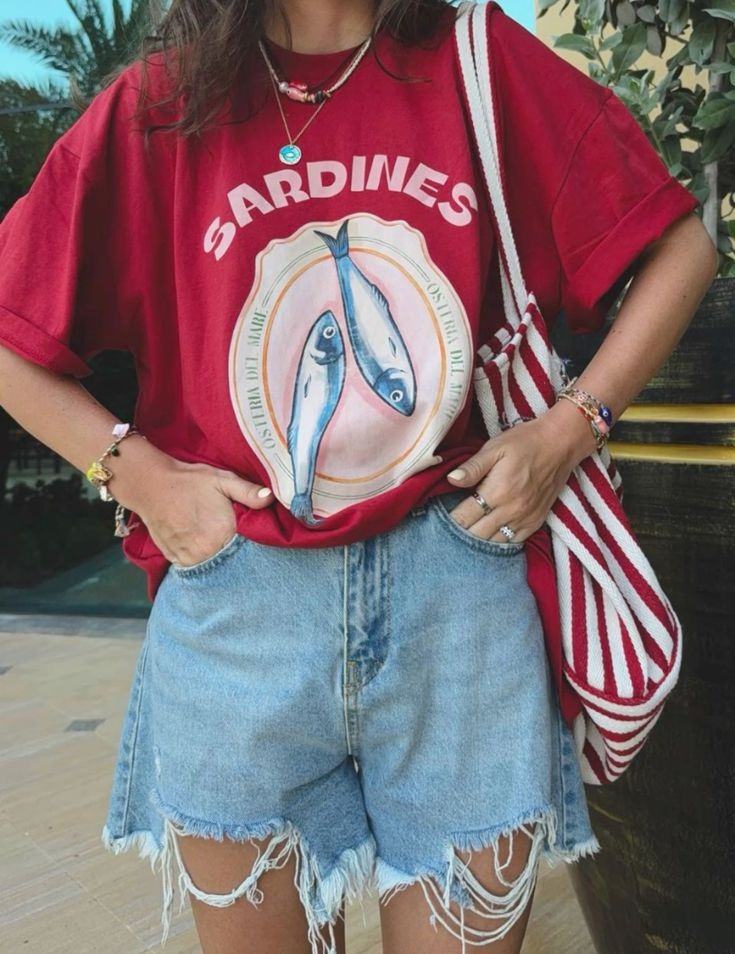

The twentieth century witnessed dramatic shifts in the function and symbolism of fashion, fueled by technological advancement, changing gender roles, and political upheavals. The women’s liberation movement challenged restrictive corsets and embraced functional clothing, like trousers and suits, which were previously taboo for women. The counterculture of the 1960s and 70s embraced tie-dye, long hair, and patchwork as symbols of peace, rebellion, and anti-establishment sentiment. In the 1980s, power dressing became a strategy for women entering corporate spaces, while punk fashion in the same decade used ripped clothing and anarchist symbols to criticize societal norms. In each case, fashion operated not as decoration, but as protest. What people wore was a direct response to what was happening in the world around them, and often, a way to demand change. Even today, fashion remains deeply political. Movements like Black Lives Matter, LGBTQ+ rights, and climate justice are reflected in sartorial choices—from slogan T-shirts to sustainable fashion practices.

Fashion is also a major driver of economic activity and innovation. Globally, the fashion industry is a multi-trillion-dollar ecosystem encompassing design, production, marketing, and retail. It fuels employment in manufacturing hubs from Bangladesh to Italy and supports creative industries in major capitals like Paris, Milan, New York, and Tokyo. Yet, this scale of operation brings ethical challenges. Fast fashion—an approach that emphasizes rapid production of cheap, trend-driven clothing—has raised serious concerns about worker exploitation, resource depletion, and environmental harm. Factories with unsafe conditions, low wages, and excessive hours often form the backbone of this industry, particularly in the Global South. The excessive use of water, chemicals, and synthetic fibers contributes to pollution, waste, and climate change. In response, there has been a growing shift toward ethical and sustainable fashion. Brands and consumers alike are reconsidering supply chains, embracing slow fashion, and championing practices that prioritize people and the planet. Second-hand markets, upcycling, and circular fashion models are gaining momentum, signaling a potential paradigm shift in how clothing is valued and consumed.

Technology is another transformative force reshaping the fashion landscape. Innovations in artificial intelligence, virtual reality, and blockchain are altering how garments are designed, produced, and distributed. Virtual fashion shows and digital avatars allow designers to present their collections without physical limitations, reducing waste and expanding creative possibilities. Augmented reality fitting rooms help consumers try on clothes without entering a store, while 3D printing enables the creation of intricate garments without sewing a single stitch. Moreover, data analytics are being used to predict trends, manage inventory, and personalize shopping experiences. These developments point toward a more efficient and interactive fashion ecosystem, though they also raise questions about authenticity, accessibility, and the future of craftsmanship. As fashion becomes increasingly digitized, it is essential to balance technological innovation with the human touch that gives clothing its soul.

Psychologically, fashion touches deep layers of the human experience. The way people dress influences not only how they are perceived, but how they feel and act. Clothing can boost confidence, shape mood, and serve as armor against the uncertainties of daily life. For some, fashion is a form of therapy—a way to cope with trauma, assert control, or reclaim a sense of identity. The phenomenon of “enclothed cognition” shows that what people wear can impact cognitive performance and emotional states. A suit may evoke professionalism and authority, while bright colors might enhance optimism and energy. These effects are not superficial; they stem from complex associations between garments, memory, culture, and self-perception.

Personal style also plays a crucial role in the development of identity, particularly during adolescence and major life transitions. Teenagers experiment with fashion to navigate peer groups, assert independence, and explore various facets of selfhood. Adults, too, use fashion to adapt to changing roles—parenthood, career shifts, aging—and to express values or aspirations. In multicultural societies, fashion becomes a site of negotiation, where people blend influences from different heritages to create new hybrid identities. Whether through subtle choices or bold statements, individuals use fashion to say who they are and who they want to become.

Yet fashion is not always a source of freedom. It can also be a source of anxiety, exclusion, and pressure. Beauty standards, body image issues, and the constant churn of trends can create unrealistic expectations and foster insecurity. Social media amplifies these effects, presenting curated images of style and success that few can attain. The rise of influencer culture has further blurred the line between authenticity and advertising, making it harder for consumers to distinguish genuine expression from commercial performance. In this environment, developing a healthy relationship with fashion requires critical awareness and conscious engagement. It involves questioning where clothes come from, who made them, what they signify, and how they make us feel.

Despite its complexities and contradictions, fashion remains a uniquely powerful domain of human creativity and connection. It offers a space where imagination meets materiality, where history converses with the future, and where individuals come together to celebrate, question, and transform the world they inhabit. From red carpets to rural villages, from runways to thrift stores, fashion is a shared language spoken in millions of dialects. It is as diverse as humanity itself, encompassing elegance and rebellion, tradition and innovation, conformity and defiance. To understand fashion is to understand people—not only how they look, but how they think, dream, and relate to one another.

In closing, fashion is not simply what we wear; it is who we are, who we have been, and who we might become. It is shaped by culture but also shapes culture in return. It responds to history but also influences its course. It is personal and political, beautiful and complicated, fleeting and enduring. To engage with fashion thoughtfully is to engage with life in all its richness, variety, and change. As long as there are people with stories to tell, identities to express, and futures to imagine, fashion will remain an essential and evolving force in the human journey.